Nature Positive / Carbon Negative: An Interview with Duke Farms

The Climate Toolkit had the chance to sit down with Jon Wagar, Deputy Executive Director of Duke Farms, a center of the Doris Duke Foundation in New Jersey, and dig deep into their two-pronged approach for climate sustainability.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

Give us the high-level view of what Duke Farms is doing in the climate sphere.

JON WAGAR:

One of the ways we’re framing what we’re doing here at Duke Farms from a climate sustainability standpoint is “Nature Positive, Carbon Negative.”

I think this applies to many other gardens and cultural institutions like us – really looking at sustainability not just from a built environment perspective, but from a nature and reciprocity perspective. Robin Wall Kimmerer speaks of this philosophy in her book Braiding Sweetgrass. Because we have 2,700 acres at Duke Farms, we need to manage our land in a way that’s both nature positive and carbon negative. So, that means driving our emissions to zero while also conducting land management and ecological restoration activities that can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. It’s important for us to think about it that way because the climate is in crisis. We need to think about it this way. The fact is, we have too much carbon dioxide in the air as it is now, and we need to drive emissions to zero while removing carbon and taking care of nature.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

How did Duke Farms begin the journey into climate sustainability?

JON WAGAR:

We have a clean energy plan that we’ve been following since 2016 that aligns with the New Jersey state goals for reduction in greenhouse gases and the Paris Agreement. We started off with energy audits and did a big carbon footprint analysis to optimize how we’re going to achieve it. The main strategies which came out of that analysis are: 1) electrifying everything, 2) greening our electricity, and 3) making our electricity system more resilient. What that’s entailed is building a new solar array with battery storage that will meet one hundred percent of our current energy needs.

JON WAGAR:

At the same time, we’re electrifying our vehicles and equipment, and importantly for the northeast, our space heating. We have a lot of old houses on campus – probably around 30 buildings that require heat. A lot of that’s natural gas or just converting them to heat pumps. Fairly straightforward. The building that’s the hardest is our greenhouse, which is a really cool old Lord & Burnham facility. Our Orchid Range and Tropical Collection, which is about 28,000 square feet, feels small compared to a lot of more famous conservatories, but it is our major conservatory, and it is energy intense. We’re running into challenges there. They don’t really have electric heating (heat pumps) yet that can maintain the temperatures we need at this point. So, we’re looking into an interim solution.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

Are you finding promising solutions on the horizon?

JON WAGAR:

We currently have what are called modulating condensing boilers here on campus. They’re 98 – 99% efficient – so if you’re going to burn natural gas, this is the way you should burn it, I think. In order to drastically reduce the carbon footprint of these natural gas boilers, we will be supplementing that with electric water heating. So, we’re designing something now where we can decrease the load on the boilers while increasing the load on our green electric grid. So again, this interim solution, we’re engineering it right now. We think we can do it, but that’s the tough nut to crack. I think with most botanical gardens that have greenhouses, that’s going to be the hardest thing to figure out from a carbon footprint perspective. Further down the line, hopefully in a few years, they will have heat pumps that can maintain the temperatures necessary for a complex indoor horticulture system.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

We’re in the exact same situation at Phipps. Our lower campus is state-of-the-art sustainable, but our upper campus, which is an historic Lord & Burnham Conservatory, is unsustainable, and we’re looking into different options, like heat pumps and geothermal.

JON WAGAR:

With greenhouses and conservatories, there may always be a need for natural gas backup. Or maybe it’s a biofuel like methane from landfills. But given the collections we have; we need to be super resilient. It’s like a hospital with multiple generators. We’re going to have to think through this issue from the horticulture and plant conservation perspective. We really need to make these systems resilient, and maybe there is a role for fuels after all, but not fossil fuels.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

Did you conduct your energy audit in-house or hire a company to perform the analysis?

JON WAGAR:

It was actually both. We hired a company, because our public utility commission had an incentive where they would pay for local governments and non-profits to hire firms to conduct energy audits. And many states have this. An engineering firm conducted the audit, but we needed help translating it and optimizing it. So, we worked with our energy consultant and one of the interesting things we found is that it’s better for us to invest in electrifying the heating rather than replacing windows. You would think efficiency and conservation would be where you should pour your money all the time. But not in this case. Rather than spending $15,000 on new windows for these old houses, or even more, we put a new $15,000 heat pump system in instead. Looking from a cost perspective, it’s less expensive. And also, from a carbon perspective as well: we have old windows from the 1890s that are beautiful, but that leak like sieves. To replace them, we need to think about the scope of emissions from manufacturing, gas, transporting – it just makes more sense to invest in sustainable energy and electrification rather than efficiency or conservation right now.

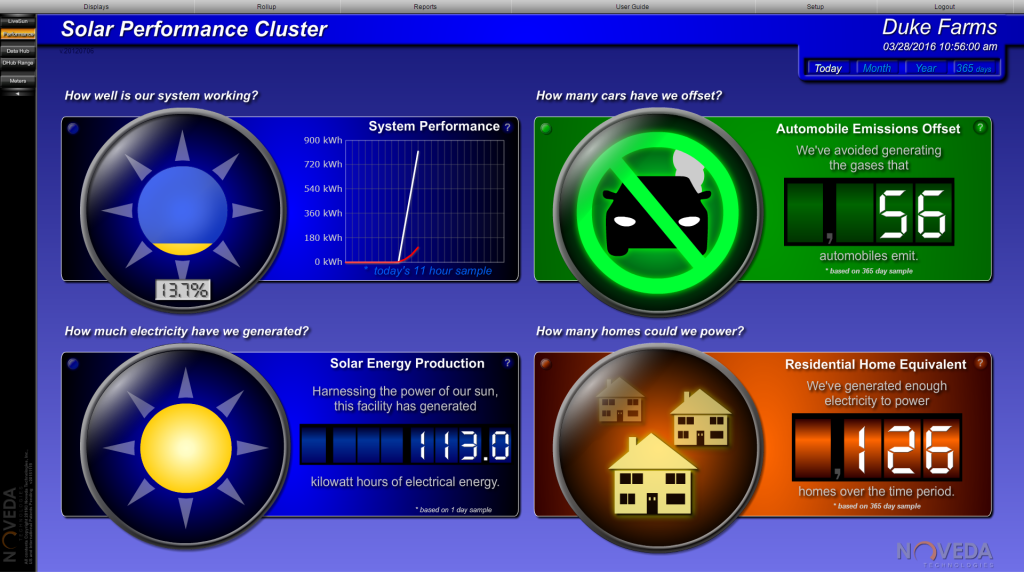

Then we had our energy consultant come in and look at our utility bills and create a model where most of the energy usage is happening and we translated this into a carbon footprint for scope 1 and scope 2 emissions. Right now, we’re taking that model and putting it into Microsoft Power BI. Microsoft BI will be able to create a real-time dashboard for facilities folks to look at what’s happening on a month-by-month basis. And then we’ll have an educational dashboard for the public showing what our real time carbon footprint is. And then an executive dashboard that’ll look at metrics. So, what the BI is doing is taking this model and making it live.

JON WAGAR:

The system is taking information from our utility bills, our finance system, and all the areas where we’re getting information about the energy we’re using, and then being able to display and create reports in one centralized place. That’s kind of a real innovation in our sustainable energy operations. We’ll have this one pane of glass where we can look and ask: How much natural gas did our orchid range and conservatory use? How much energy did our electric vehicle use this month? How much solar production was there? Because there are so many data streams coming in, the BI will take all the information from the smart meters across campus and be able to bring it all together in one spot. And that’s happening now as we speak.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

That sounds truly next level.

JON WAGAR:

We’re excited about it. Because every single institution has these streams of data, right? We’re finding that working with our finance department or with the local utility, we can start to string it together to create this really clear picture of what’s going on – not just on an annual basis, but on a continuing basis.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

Do you include Scope 3 in your emissions analysis, or solely focus on Scope 1 and 2?

JON WAGAR:

We’ve done a lot of thought about particularly Scope 3, because those are the sort of things that are difficult for us to get a handle on. When we did our carbon footprint analysis, we decided to look at our visitors, where they came from and their emissions. If we just looked at our emissions and the carbon absorbed through natural climate solutions on our land base, we would be carbon negative. But then calculating the emissions from our visitors – it blew it out of the water as far as our carbon emissions. That’s why we went ahead and got a grant to develop these DC fast chargers – which will be operating by the end of the month – and a bunch of new level two chargers.

JON WAGAR:

Scope 3 is the most challenging for us. I really believe that we need to explicitly address it, because otherwise we can sort of trick ourselves into saying we’re carbon neutral or net-zero without accounting for Scope 3. When you start to address Scope 3, however, it widens your perspective and the actions that you should be taking – like building a DC fast-charger or looking at our environmental education programs and promoting carbon negative actions. So, again, I think with this wider sort of carbon footprint analysis, we all need to look at our carbon and energy systems while addressing Scope 3 and being explicit that it’s an issue. Scope 1 and Scope 2 – it’s fairly easy to put an impact number on what you’re emitting, and over time looking at reducing it. With Scope 1, it’s just what you’re burning on site, fossil-fuel wise. And then with Scope 2, it’s looking at your energy grid and the electricity you’re pulling from the grid. That stuff is very quantifiable. But Scope 3 is much more qualitative, because there are errors; you don’t know if you’re counting something twice. The whole life cycle analysis is just so complex.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

How have you begun to tackle your Scope 3 analysis?

JON WAGAR:

We have a researcher at Rutgers University we’re collaborating with – she’s working to complete a life cycle carbon footprint analysis, and her specialty is Scope 3. We should have that by the end of the year. And then we’ll have to figure out how we address it, how we communicate it. There are certainly things we won’t be able to do or address – unless we stop getting packages from Amazon operationally, for instance. But then there are things we will be able to do. At any rate, our thoughts have evolved a lot in doing this and thinking more broadly about emissions. Even though unfortunately what that means is Duke Farms won’t show as carbon negative anytime soon. As far as the gross carbon emissions, we could be net negative eventually. But the gross carbon emissions related to this site, and the gross greenhouse gas emissions related to all of our sites, need to be addressed.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

Do you have full institutional support for your strategies?

JON WAGAR:

We have what we’re calling a Catalyst Initiative. There are three of us within Doris Duke Foundation that are talking a lot about this and elevating it within the organization. It’s our Executive Director Margaret Waldock, and our Facilities & Technology Manager Jim Hanson; we’ve been the ones doing the most thinking about it. However, unlike some botanic gardens and other institutions, our mission is sustainability. So, there’s not a lot of pushback. We’re also forming partnerships with similar sized institutions to figure out the barriers to quick implementation and acceleration of clean energy. What can we do differently with the permitting to make sure that solar happens more quickly? Or battery storage and resilience. Partners and educational institutions can extend our reach and help to influence the speed at which the energy transition is happening.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

Is the goal at Duke Farms to become a demonstration campus for other larger institutions – folks with huge amounts of acreage – and be a guidepost for how to adopt best practices in the climate sustainability space?

JON WAGAR:

We have a platform for influencing the acceleration of clean energy. Of course, we’re not doing everything here. We don’t have offshore wind, for example. But I think what we’re doing on the ground gives us a real seat at the table to help influence the conversation. I see us as being leaders in pushing this forward and using our facility as a platform – not just because we have the technology here and we’re putting it together in a neat way, but also that we have a great spot for convening and bringing people together to talk about these issues. Using our collective experience as a base to be able to create leverage and eventually bring folks together at the national level. We really see ourselves as trying to have a leadership position, at least here in New Jersey locally. Because a lot of these issues are very local, right?

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

Can you tell me about the land regeneration techniques that you’re doing at Duke Farms?

JON WAGAR:

So, we have a little over 2,700 acres, and we’ve done a lot of restoration. Much of it was agricultural land in sort of inappropriate areas – so flood plains that would get flooded once every two years or so. What we’ve done is, we work with the federal government, with NRCS, and put easements on about 500 acres along the flood plain — the Raritan River — and then have been restoring it back to native riparian habitat with some innovative funding sources called natural resource damage settlement. We’ve also brought outside money into converting what was corn and soy back into what was – way before even the Dutch farmers were here in the early 1700s – riparian forest land. And that’s really important because the Raritan River is the public water supply. It’s prone to a lot of flooding. So that restoration will help slow the river down.

JON WAGAR:

We also have agricultural fields that we manage – we have a herd of cattle in an agroecology farming program that we’re managing for grassland birds and grassland pasture restoration work. We have upland forests where we’re doing invasive species control. We have an active deer management program, focused on controlling invasives, promoting natives and natural ecosystem processes. So, we have all these restoration projects that have been going on for years. Three years ago, we started a research project with Rutgers University, and we paid them to help us figure out what the carbon baseline was for all the restoration projects we were doing. What they’ve done is they’ve measured the soil carbon in all the soils, carbon in the trees, and they’re looking at carbon fluxes with these Eddy-Covariance Flux Towers.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

Tell us more about that.

JON WAGAR:

These are towers that’ll show you the carbon fluxes throughout the year in ecosystems. We have several, as well as sap flow meters that are measuring growth of trees. So, we’re doing a lot of accurate scientific measurement of how much carbon this land is sequestering. And then also looking at management practices and how that affects it. For example, we’re looking at how the addition of biochar in soils increases the soil carbon and sequestration, or how changes in land management practices like reforestation or planting native plants and shrubs will change the carbon intake. It’s more than the baseline – we’re conducting experiments where we’re doing actual land management techniques to see how that may be able to increase the carbon content of this soil.

JON WAGAR:

However, what you run into everywhere is this idea that ‘nature positive’ isn’t just about carbon. We have some of the best endangered grassland habitat in the state here in our agricultural fields – native warm season grasses for the most part. And, our idea is, cows can help maintain that. In fact, as we’re putting animals back on land, we’re finding that the carbon rates in the soil are going up. Even though cows obviously emit a lot of methane, it’s actually having a real positive impact on soil health and quality. It’s going to be interesting to see the numbers. We’re thinking that a lot of the methane is being offset by the fact that these lands are being treated much better than they were in the past, as far as nutrient cycles.

Now, if we were to maximize for carbon sequestration, we’d plant that all up in trees. Right? But growing trees would destroy the grassland habitat. This brings us back to the idea of nature positive. These are trade-offs we all have to make in managing lands or properties. At Duke Farms, we’re saying we are not going to maximize carbon uptake because we have grassland habitat, we have cows, we have birds; and endangered birds is really our conservation target. So, we’re trying to use cattle to manage these habitats rather than mowing, which has the added benefit of adding carbon to the soil. It is a very cool agroecology system that might be able to be mimicked other places for grass and birds.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

I love thinking about this opportunity at Duke Farms for demonstration of best practices – especially with rotational grazing. Has there been any conversation about connecting with industrial farmers, or folks that practice non-ecological ways of farming, and showing them that rotational grazing is a very beneficial practice for managing both cattle and land?

JON WAGAR:

We’re working now with a few like-minded farmers around the area – there are a lot of young farmers coming up that are inheriting family farms and don’t want to do standard row crops. There’s a real opportunity, but there are also some bottlenecks. For example, we don’t have infrastructure at Duke Farms for a slaughterhouse and butchers here. We have to take everything to Pennsylvania, which is costly. So, all of our cattle get processed there, and then returned for our farm to fork café operations. We’ve been donating a lot of it as well to food banks, which has been great because we’re able to offer super high-quality, grass-fed beef, that’s been finished on grain. It’ll get finished by someone who is a specialty finisher for grass-fed beef – and then Duke Farms works on co-marketing the product with them. The idea is to help the industry along too, looking at it within this larger context. Then we can help hopefully jumpstart this movement and advocate for best practices. And I think we’re realizing there’s a huge market, especially in New Jersey, for local beef that’s grass-fed and bird friendly – and that it can demand a real premium.

And that’s the thing with grass and bird habitats. You want to maintain certain conditions of the pastures, certain grass heights, and you want to be moving the cows quite frequently, which is different than most beef cattle operations. And I think what we’re showing at Duke Farms is that you can do both and get more highly productive pastures, which is what the birds want and what the cows want. So, we’re doing this real intensively managed grazing system. We’ve been doing it for a while, and we’re just refining the business model now. But again, it’s one of these trade-offs. You wouldn’t have cows if you were trying to really maximize carbon sequestration.

CLIMATE TOOLKIT:

I wonder if there’s an argument to be made about this. Potentially, yes, you’re not maximizing carbon sequestration locally in your fields – yet by doing outreach and providing demonstration of how to properly manage cattle and grasslands together, perhaps you make a greater impact. If you had the intention to connect with 100 cattle farmers, and these 100 farms decided to adopt rotational grazing on their properties, then suddenly you have a much larger carbon sequestration impact than you would just on your one localized area.

JON WAGAR:

Absolutely. We have to realize the fact that people aren’t going to stop eating meat. Right? However, if there are more sustainable ways to raise that meat, more healthy and humane ways that we can demonstrate, that’s probably a good thing. You can really use cows to improve grassland habitat and soil if you do it right. So that’s the nature-positive aspect. We’re doing tons of restoration, a lot of agroecology, but not everything is going to be for maximizing carbon sequestration. I think that’s a really good point that sometimes people miss. We can get too wrapped up in ideas: climate, carbon, sequestration… But then we sort of miss the nature piece. Our benefactors at Duke Farms basically said that this property must be used for the benefit of wildlife and agriculture. So, we take what Doris Duke said and try to interpret it within a modern-day context. And this is where we’ve landed: being nature positive and carbon negative.

Recent Comments