טבע חיובי / פחמן שלילי: ראיון עם Duke Farms

ל-Climate Toolkit הייתה הזדמנות לשבת עם ג'ון וואגר, סגן המנהל של Duke Farms, מרכז של קרן דוריס דיוק בניו ג'רזי, ולחפור עמוק בגישה הדו-צדדית שלהם לקיימות אקלימית.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

תן לנו את התצוגה ברמה גבוהה של מה שדוכס פארמס עושה בתחום האקלים.

ג'ון וואגר:

אחת הדרכים שבהן אנחנו ממסגרים את מה שאנחנו עושים כאן ב-Duke Farms מנקודת מבט של קיימות אקלימית היא "טבע חיובי, פחמן שלילי."

אני חושב שזה חל על הרבה גנים ומוסדות תרבות אחרים כמונו - באמת מסתכלים על קיימות לא רק מנקודת מבט של סביבה בנויה, אלא מנקודת מבט של טבע והדדיות. רובין וול קימרר מדברת על הפילוסופיה הזו בספרה קליעה של Sweetgrass. מכיוון שיש לנו 2,700 דונם ב-Duke Farms, אנחנו צריכים לנהל את האדמה שלנו בצורה שהיא גם חיובית לטבע וגם שלילית לפחמן. אז, זה אומר להעלות את הפליטות שלנו לאפס תוך ביצוע פעילויות ניהול קרקע ושיקום אקולוגי שיכולים להסיר פחמן דו חמצני מהאטמוספרה. חשוב לנו לחשוב על זה ככה כי האקלים במשבר. אָנוּ צוֹרֶך לחשוב על זה ככה. העובדה היא, שיש לנו יותר מדי פחמן דו חמצני באוויר כפי שהוא עכשיו, ועלינו להעלות את הפליטות לאפס תוך הסרת פחמן וטיפול בטבע.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

כיצד התחילה Duke Farms את המסע לקיימות אקלימית?

ג'ון וואגר:

יש לנו א תוכנית אנרגיה נקייה שאנחנו עוקבים אחריו מאז 2016 שמתיישר עם יעדי מדינת ניו ג'רזי להפחתת גזי חממה הסכם פריז. התחלנו עם ביקורות אנרגיה ועשינו ניתוח טביעת רגל פחמן גדול כדי לייעל את האופן שבו אנחנו הולכים להשיג זאת. האסטרטגיות העיקריות שיצאו מניתוח זה הן: 1) חשמול הכל, 2) ירק החשמל שלנו ו-3) הפיכת מערכת החשמל שלנו לגמישה יותר. מה שזה כרוך הוא בניית מערך סולארי חדש עם אחסון סוללות שיענה על מאה אחוז מצרכי האנרגיה הנוכחיים שלנו.

ג'ון וואגר:

במקביל, אנחנו מחשמלים את כלי הרכב והציוד שלנו, וחשוב לצפון מזרח, חימום החלל שלנו. יש לנו הרבה בתים ישנים בקמפוס - כנראה בסביבות 30 בניינים שדורשים חום. הרבה מזה הוא גז טבעי או סתם המרתם למשאבות חום. די ישר. הבניין שהכי קשה הוא החממה שלנו, שהיא מתקן ישן ומגניב לורד אנד ברנהאם. טווח הסחלבים והאוסף הטרופי שלנו, ששטחו כ-28,000 רגל מרובע, מרגיש קטן בהשוואה להרבה חממות מפורסמות יותר, אבל זה החממה העיקרית שלנו, והיא עוצמתית באנרגיה. אנחנו נתקלים באתגרים שם. אין להם עדיין חימום חשמלי (משאבות חום) שיכול לשמור על הטמפרטורות שאנחנו צריכים בשלב זה. אז, אנחנו בוחנים פתרון ביניים.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

האם אתה מוצא פתרונות מבטיחים באופק?

ג'ון וואגר:

כרגע יש לנו מה שנקרא דודי עיבוי מווסתים כאן בקמפוס. הם יעילים ב-98 - 99% - אז אם אתה מתכוון לשרוף גז טבעי, זו הדרך שבה אתה צריך לשרוף אותו, אני חושב. על מנת להפחית באופן דרסטי את טביעת הרגל הפחמנית של דודי הגז הטבעי הללו, נשלים זאת עם חימום מים חשמלי. אז, אנחנו מתכננים משהו עכשיו שבו נוכל להפחית את העומס על הדוודים תוך הגדלת העומס על רשת החשמל הירוקה שלנו. אז שוב, פתרון הביניים הזה, אנחנו מהנדסים אותו עכשיו. אנחנו חושבים שאנחנו יכולים לעשות את זה, אבל זה האגוז שקשה לפצח. אני חושב שברוב הגנים הבוטניים שיש להם חממות, זה יהיה הדבר הקשה ביותר להבין מנקודת מבט של טביעת רגל פחמנית. בהמשך הקו, בתקווה שבעוד כמה שנים, יהיו להם משאבות חום שיוכלו לשמור על הטמפרטורות הדרושות למערכת גננות מקורה מורכבת.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

אנחנו באותו מצב בדיוק בפיפס. הקמפוס התחתון שלנו הוא בר-קיימא חדיש, אבל הקמפוס העליון שלנו, שהוא קונסרבטוריון היסטורי של לורד אנד ברנהאם, אינו בר-קיימא, ואנחנו בוחנים אפשרויות שונות, כמו משאבות חום וגיאותרמיות.

ג'ון וואגר:

עם חממות וחממות, ייתכן שתמיד יהיה צורך בגיבוי גז טבעי. או אולי זה דלק ביולוגי כמו מתאן ממזבלות. אבל בהתחשב באוספים שיש לנו; אנחנו צריכים להיות עמידים במיוחד. זה כמו בית חולים עם מספר גנרטורים. נצטרך לחשוב על הנושא הזה מנקודת המבט של גננות ושימור צמחים. אנחנו באמת צריכים להפוך את המערכות האלה לגמישות, ואולי בכל זאת יש תפקיד לדלקים, אבל לא לדלקים מאובנים.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

האם ערכת את ביקורת האנרגיה שלך בבית או שכרת חברה שתבצע את הניתוח?

ג'ון וואגר:

זה היה בעצם שניהם. שכרנו חברה, כי לנציבות השירות הציבורי שלנו היה תמריץ שבו הם ישלמו לממשלות מקומיות ולמלכ"רים לשכור חברות לביצוע ביקורות אנרגיה. ולהרבה מדינות יש את זה. חברת הנדסה ערכה את הביקורת, אבל היינו צריכים עזרה בתרגום וייעול שלה. לכן, עבדנו עם יועץ האנרגיה שלנו ואחד הדברים המעניינים שמצאנו הוא שעדיף לנו להשקיע בחשמול החימום ולא בהחלפת חלונות. היית חושב שיעילות ושימור יהיו המקום שבו אתה צריך לשפוך את כספך כל הזמן. אבל לא במקרה הזה. במקום להוציא $15,000 על חלונות חדשים עבור הבתים הישנים האלה, או אפילו יותר, הכנסנו במקום מערכת משאבת חום חדשה $15,000. בהסתכלות מנקודת מבט של עלות, זה פחות יקר. וגם, גם מנקודת מבט של פחמן: יש לנו חלונות ישנים משנות ה-90 שהם יפים, אבל דולפים כמו מסננות. כדי להחליף אותם, אנחנו צריכים לחשוב על היקף הפליטות מייצור, גז, הובלה - זה פשוט הגיוני יותר להשקיע באנרגיה בת קיימא ובחשמל במקום ביעילות או בשימור כרגע.

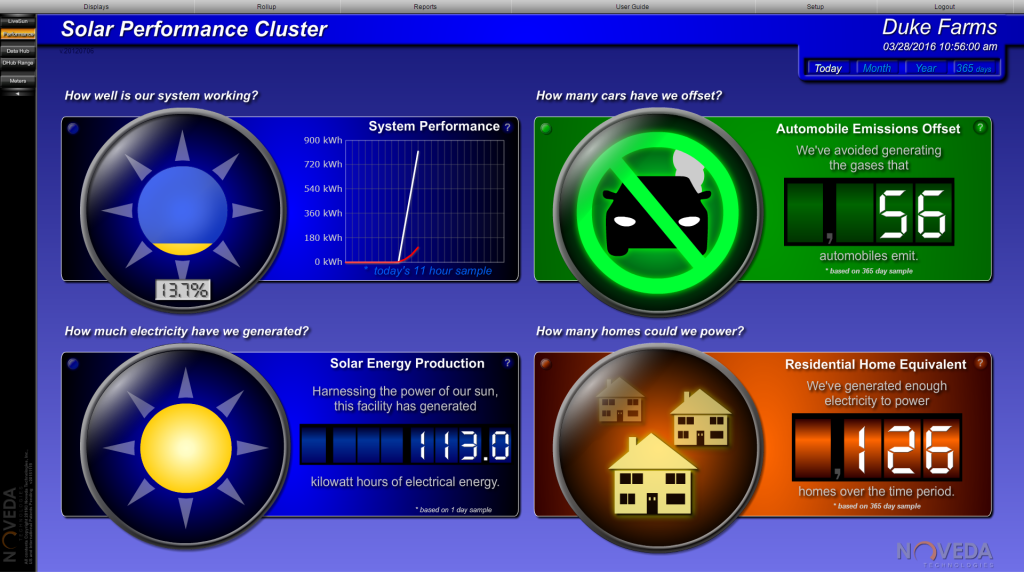

לאחר מכן הזמנו את יועץ האנרגיה שלנו, הסתכל על חשבונות החשמל שלנו ויצרנו מודל שבו רוב השימוש באנרגיה מתרחש ותרגמנו את זה לטביעת רגל פחמנית עבור פליטות scope 1 ו-scope 2. כרגע, אנחנו לוקחים את המודל הזה ומכניסים אותו Microsoft Power BI. Microsoft BI יוכל ליצור לוח מחוונים בזמן אמת עבור אנשי מתקנים שיסתכלו על מה שקורה על בסיס חודשי. ואז יהיה לנו לוח מחוונים חינוכי לציבור שיראה מהי טביעת הרגל הפחמנית שלנו בזמן אמת. ואז לוח מחוונים מנהלים שיסתכל על מדדים. אז מה שה-BI עושה זה לקחת את המודל הזה ולהפוך אותו לפעיל.

ג'ון וואגר:

המערכת לוקחת מידע מחשבונות החשמל שלנו, ממערכת הכספים שלנו ומכל האזורים שבהם אנו מקבלים מידע על האנרגיה שאנו משתמשים בהם, ולאחר מכן מסוגלת להציג וליצור דוחות במקום מרוכז אחד. זה סוג של חידוש אמיתי בפעילות האנרגיה בת-קיימא שלנו. תהיה לנו זכוכית אחת שבה נוכל להסתכל ולשאול: בכמה גז טבעי השתמשו במגוון הסחלבים והחממה שלנו? כמה אנרגיה השתמש הרכב החשמלי שלנו החודש? כמה ייצור סולארי היה? מכיוון שיש כל כך הרבה זרמי נתונים נכנסים, ה-BI ייקח את כל המידע מהמונים החכמים ברחבי הקמפוס ויוכל לרכז את הכל במקום אחד. וזה קורה עכשיו בזמן שאנחנו מדברים.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

זה נשמע באמת שלב הבא.

ג'ון וואגר:

אנחנו מתרגשים מזה. כי לכל מוסד יש את זרמי הנתונים האלה, נכון? אנחנו מגלים שבעבודה עם מחלקת הכספים שלנו או עם חברת החשמל המקומית, אנחנו יכולים להתחיל לחבר את זה יחד כדי ליצור תמונה ברורה באמת של מה שקורה - לא רק על בסיס שנתי, אלא על בסיס מתמשך.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

האם אתה כולל היקף 3 בניתוח הפליטות שלך, או להתמקד אך ורק ב היקף 1 ו-2?

ג'ון וואגר:

עשינו מחשבה רבה במיוחד על Scope 3, כי אלה מסוג הדברים שקשה לנו להתמודד איתם. כשעשינו את ניתוח טביעת הרגל הפחמנית שלנו, החלטנו להסתכל על המבקרים שלנו, מהיכן הם הגיעו והפליטות שלהם. אם רק היינו מסתכלים על הפליטות שלנו ועל הפחמן שנספג באמצעות פתרונות אקלים טבעיים על הבסיס היבשתי שלנו, היינו שליליים לפחמן. אבל אז חישוב הפליטות מהמבקרים שלנו - זה הוציא אותו מהמים עד לפליטת הפחמן שלנו. זו הסיבה שהקדמנו וקיבלנו מענק לפיתוח מטענים מהירים DC אלה – שיפעלו עד סוף החודש – וחבורה של מטענים חדשים ברמה שתיים.

ג'ון וואגר:

סקופ 3 הוא המאתגר ביותר עבורנו. אני באמת מאמין שאנחנו צריכים להתייחס לזה במפורש, כי אחרת אנחנו יכולים להערים על עצמנו לומר שאנחנו ניטרליים פחמן או אפס נטו מבלי לקחת בחשבון את סקופ 3. כאשר אתה מתחיל להתייחס לסקופ 3, עם זאת, זה מרחיב את נקודת המבט שלך והפעולות שעליך לבצע - כמו בניית מטען מהיר של DC או התבוננות בתוכניות החינוך הסביבתי שלנו וקידום פעולות פחמן שליליות. אז, שוב, אני חושב שעם סוג רחב יותר זה של ניתוח טביעת רגל פחמן, כולנו צריכים להסתכל על מערכות הפחמן והאנרגיה שלנו תוך התייחסות להיקף 3 ולהיות מפורש שזו בעיה. סקופ 1 ו-scope 2 - די קל לשים מספר השפעה על מה שאתה פולט, ועם הזמן להסתכל על צמצום. עם Scope 1, זה בדיוק מה שאתה שורף באתר, מבחינת דלק מאובנים. ואז עם סקופ 2, זה מסתכל על רשת האנרגיה שלך ועל החשמל שאתה שואב מהרשת. החומר הזה מאוד ניתן לכימות. אבל סקופ 3 הוא הרבה יותר איכותי, כי יש שגיאות; אתה לא יודע אם אתה סופר משהו פעמיים. כל ניתוח מחזור החיים הוא פשוט כל כך מורכב.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

איך התחלת להתמודד עם ניתוח Scope 3 שלך?

ג'ון וואגר:

יש לנו חוקרת באוניברסיטת רוטגרס שאנחנו משתפים פעולה איתה - היא עובדת כדי להשלים ניתוח טביעת רגל פחמן במחזור החיים, וההתמחות שלה היא Scope 3. אנחנו צריכים לקבל את זה עד סוף השנה. ואז נצטרך להבין איך אנחנו מתייחסים לזה, איך אנחנו מתקשרים את זה. בהחלט יש דברים שלא נוכל לעשות או לטפל בהם - אלא אם נפסיק לקבל חבילות מאמזון באופן תפעולי, למשל. אבל אז יש דברים שנוכל לעשות. בכל מקרה, המחשבות שלנו התפתחו רבות בעשייה זו וחשיבה רחבה יותר על פליטות. למרות שלמרבה הצער, המשמעות של זה היא ש-Duke Farms לא יוצגו כפחמן שלילי בזמן הקרוב. לגבי פליטת הפחמן הגולמית, אנחנו יכולים להיות שליליים נטו בסופו של דבר. אבל יש להתייחס לפליטות הפחמן הגולמיות הקשורות לאתר הזה, ולפליטת גזי החממה הגולמית הקשורה לכל האתרים שלנו.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

האם יש לך תמיכה מוסדית מלאה באסטרטגיות שלך?

ג'ון וואגר:

יש לנו מה שאנחנו מכנים יוזמת קטליסט. אנחנו שלושה בקרן דוריס דיוק שמדברים הרבה על זה ומגבירים את זה בתוך הארגון. זה המנהלת המבצעת שלנו, מרגרט וולדוק, ומנהל המתקנים והטכנולוגיה שלנו, ג'ים הנסון; אנחנו אלה שחשבו על זה הכי הרבה. עם זאת, שלא כמו כמה גנים בוטניים ומוסדות אחרים, המשימה שלנו היא קיימות. אז, אין הרבה דחיפות. אנחנו גם יוצרים שותפויות עם מוסדות בגודל דומה כדי להבין את החסמים ליישום מהיר ולהאצה של אנרגיה נקייה. מה אנחנו יכולים לעשות אחרת עם ההיתר כדי לוודא שהשמש מתרחשת מהר יותר? או אחסון וגמישות סוללה. שותפים ומוסדות חינוך יכולים להרחיב את טווח ההגעה שלנו ולעזור להשפיע על המהירות שבה מתרחש מעבר האנרגיה.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

האם המטרה ב-Duke Farms היא להפוך לקמפוס הדגמה עבור מוסדות גדולים אחרים - אנשים עם כמויות אדירות של שטחים - ולהוות מדריך כיצד לאמץ שיטות עבודה מומלצות בתחום קיימות האקלים?

ג'ון וואגר:

יש לנו פלטפורמה להשפעה על האצת אנרגיה נקייה. כמובן, אנחנו לא עושים הכל כאן. אין לנו רוח ימית, למשל. אבל אני חושב שמה שאנחנו עושים בשטח נותן לנו מקום אמיתי ליד השולחן כדי לעזור להשפיע על השיחה. אני רואה אותנו כמובילים בדחיפה קדימה ושימוש במתקן שלנו כפלטפורמה - לא רק בגלל שיש לנו את הטכנולוגיה כאן ואנחנו מחברים אותה בצורה מסודרת, אלא גם שיש לנו מקום מצוין להתכנס ולהביא אנשים יחד כדי לדבר על הנושאים האלה. שימוש בניסיון הקולקטיבי שלנו כבסיס כדי להיות מסוגל ליצור מינוף ובסופו של דבר לקרב אנשים ברמה הלאומית. אנחנו באמת רואים את עצמנו כמנסים לקבל עמדת מנהיגות, לפחות כאן בניו ג'רזי מקומית. כי הרבה מהנושאים האלה הם מאוד מקומיים, נכון?

ערכת כלי אקלים:

אתה יכול לספר לי על טכניקות התחדשות הקרקע שאתה עושה ב-Duke Farms?

ג'ון וואגר:

אז, יש לנו קצת יותר מ-2,700 דונם, ועשינו הרבה שיקום. חלק גדול ממנה היה קרקע חקלאית במעין אזורים לא מתאימים - אז מישורי שיטפונות שהיו מוצפים אחת לשנתיים בערך. מה שעשינו זה שאנחנו עובדים עם הממשלה הפדרלית NRCS, ושימו הקלות על כ-500 דונם לאורך מישור השיטפונות - נהר רריטן - ולאחר מכן החזרו אותו לבית גידול גדות עם כמה מקורות מימון חדשניים הנקראים יישוב נזקי משאבי טבע. הבאנו גם כסף מבחוץ להמרת מה שהיה תירס וסויה בחזרה למה שהיה - הרבה לפני שאפילו החקלאים ההולנדים היו כאן בתחילת המאה ה-17 - אדמת יער גדות. וזה באמת חשוב כי נהר רריטן הוא אספקת המים הציבורית. הוא מועד להצפות רבות. אז שיקום זה יעזור להאט את הנהר.

ג'ון וואגר:

יש לנו גם שדות חקלאיים שאנו מנהלים - יש לנו עדר בקר בתוכנית חקלאות אגרואקולוגית שאנו מנהלים עבור ציפורים ועבודות שיקום מרעה. יש לנו יערות על הקרקע שבהם אנחנו מבצעים בקרת מינים פולשים. יש לנו תוכנית פעילה לניהול צבאים, המתמקדת בשליטה בפולשים, קידום ילידים ותהליכים טבעיים של המערכת האקולוגית. אז, יש לנו את כל פרויקטי השיקום האלה שנמשכים כבר שנים. לפני שלוש שנים, התחלנו פרויקט מחקר עם אוניברסיטת רוטגרס, ושילמנו להם כדי לעזור לנו להבין מה היה קו הבסיס של הפחמן עבור כל פרויקטי השיקום שעשינו. מה שהם עשו זה שהם מדדו את פחמן הקרקע בכל הקרקעות, פחמן בעצים, והם מסתכלים על שטפי פחמן עם אלה אדי-קובאריאנס מגדלי השטף.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

ספר לנו עוד על זה.

ג'ון וואגר:

אלו מגדלים שיראו לכם את שטפי הפחמן לאורך השנה במערכות אקולוגיות. יש לנו מספר, כמו גם מדי זרימת מוהל שמודדים צמיחה של עצים. אז, אנחנו עושים הרבה מדידות מדעיות מדויקות של כמה פחמן האדמה הזו קולטת. ואז גם מסתכלים על שיטות ניהול ואיך זה משפיע עליו. לדוגמה, אנו בוחנים כיצד הוספה של ביוצ'אר בקרקעות מגבירה את פחמן הקרקע ותפיסת הקרקע, או כיצד שינויים בפרקטיקות של ניהול קרקע כמו ייעור מחדש או שתילת צמחים ושיחים מקומיים ישנו את צריכת הפחמן. זה יותר מקו הבסיס - אנחנו עורכים ניסויים שבהם אנחנו עושים טכניקות ניהול קרקע ממשיות כדי לראות איך זה עשוי להגדיל את תכולת הפחמן של האדמה הזו.

ג'ון וואגר:

עם זאת, מה שאתה נתקל בו בכל מקום הוא הרעיון ש'טבע חיובי' אינו קשור רק לפחמן. יש לנו כמה מבתי הגידול הטובים ביותר של שטחי העשב שנמצאים בסכנת הכחדה במדינה כאן בשדות החקלאיים שלנו - עשבים מקומיים של העונה החמה לרוב. והרעיון שלנו הוא, פרות יכולות לעזור לשמור על זה. למעשה, כאשר אנו מחזירים בעלי חיים על היבשה, אנו מגלים ששיעורי הפחמן באדמה עולים. למרות שפרות כמובן פולטות הרבה מתאן, למעשה יש לזה השפעה חיובית אמיתית על בריאות הקרקע ואיכותו. יהיה מעניין לראות את המספרים. אנחנו חושבים שהרבה מהמתאן מתקזז על ידי העובדה שהשטחים האלה מטופלים הרבה יותר טוב ממה שהיו בעבר, בכל הנוגע למחזורי חומרי הזנה.

עכשיו, אם היינו ממקסמים את קיבוע הפחמן, היינו שותלים את כל זה בעצים. יָמִינָה? אבל גידול עצים יהרוס את בית הגידול של עשב. זה מחזיר אותנו לרעיון של טבע חיובי. אלו פשרות שכולנו צריכים לעשות בניהול קרקעות או נכסים. ב-Duke Farms, אנחנו אומרים שאנחנו לא מתכוונים למקסם את ספיגת הפחמן כי יש לנו בית גידול למשטחי עשב, יש לנו פרות, יש לנו ציפורים; וציפורים בסכנת הכחדה היא באמת יעד השימור שלנו. אז, אנחנו מנסים להשתמש בבקר כדי לנהל את בתי הגידול האלה במקום לכסח, שיש לו יתרון נוסף של הוספת פחמן לאדמה. זה מגניב מאוד מערכת אגרואקולוגיה שאולי ניתן יהיה לחקות מקומות אחרים עבור דשא וציפורים.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

אני אוהב לחשוב על ההזדמנות הזו ב-Duke Farms להדגמה של שיטות עבודה מומלצות - במיוחד עם מרעה סיבובית. האם הייתה שיחה כלשהי על חיבור עם חקלאים תעשייתיים, או אנשים העוסקים בדרכים לא אקולוגיות של חקלאות, ולהראות להם שמרעה סיבובית היא שיטה מועילה מאוד לניהול בקר ואדמה כאחד?

ג'ון וואגר:

אנחנו עובדים עכשיו עם כמה חקלאים בעלי דעות דומות באזור - יש הרבה חקלאים צעירים שמגיעים שיורשים חוות משפחתיות ולא רוצים לעשות גידולי שורות סטנדרטיים. יש הזדמנות אמיתית, אבל יש גם כמה צווארי בקבוק. למשל, אין לנו ב-Duke Farms תשתית למשחטה ולקצבים כאן. אנחנו צריכים לקחת הכל לפנסילבניה, וזה יקר. אז כל הבקר שלנו עובר עיבוד שם, ואז חזר לחווה שלנו כדי לחלק את פעילות בתי הקפה. תרמנו הרבה ממנו גם לבנקי מזון, וזה היה נהדר כי אנחנו מסוגלים להציע בשר בקר סופר-איכותי, מוזן דשא, שגמר על דגנים. זה יסתיים על ידי מישהו שהוא מומחה לגימור בשר בקר מוזן דשא - ואז דיוק פארמס עובד על שיווק משותף של המוצר איתם. הרעיון הוא לעזור לתעשייה גם כן, להסתכל עליה בהקשר רחב יותר זה. אז נוכל לעזור בתקווה להזניק את התנועה הזו ולעודד שיטות עבודה מומלצות. ואני חושב שאנחנו מבינים שיש שוק ענק, במיוחד בניו ג'רזי, לבשר בקר מקומי שמוזן בעשב וידידותי לציפורים - ושהוא יכול לדרוש פרמיה אמיתית.

וזה העניין עם בתי גידול של דשא וציפורים. אתה רוצה לשמור על תנאים מסוימים של המרעה, גבהים מסוימים של דשא, ואתה רוצה להזיז את הפרות בתדירות גבוהה למדי, וזה שונה מרוב פעולות הבקר לבשר. ואני חושב שמה שאנחנו מראים ב-Duke Farms זה שאתה יכול לעשות את שניהם ולהשיג שטחי מרעה פרודוקטיביים יותר, וזה מה שהציפורים רוצות ומה שהפרות רוצות. אז, אנחנו עושים את מערכת המרעה האמיתית המנוהלת באינטנסיביות. עשינו את זה כבר זמן מה, ואנחנו רק משכללים את המודל העסקי עכשיו. אבל שוב, זה אחד מההפרעות האלה. לא היו לך פרות אם היית מנסה באמת למקסם את ריבוד הפחמן.

ערכת כלי אקלים:

אני תוהה אם יש טענה בנושא. פוטנציאלי, כן, אינך ממקסם את קיבוע הפחמן המקומי בשדות שלך - אך על ידי ביצוע הסברה ומתן הדגמה כיצד לנהל נכון בקר ואדמות מרעה יחד, אולי אתה יוצר השפעה גדולה יותר. אם הייתה לך כוונה להתחבר ל-100 חקלאי בקר, ו-100 החוות האלה החליטו לאמץ מרעה סיבובית על הנכסים שלהן, אז פתאום יש לך השפעת כיבוש פחמן הרבה יותר גדולה מזו שהיית עושה רק על האזור המקומי האחד שלך.

ג'ון וואגר:

בְּהֶחלֵט. אנחנו צריכים להבין את העובדה שאנשים לא הולכים להפסיק לאכול בשר. יָמִינָה? עם זאת, אם יש דרכים ברות קיימא יותר לגדל את הבשר הזה, דרכים בריאות ואנושיות יותר שאנחנו יכולים להדגים, זה כנראה דבר טוב. אתה באמת יכול להשתמש בפרות כדי לשפר את בית הגידול והקרקע של שטח העשב אם אתה עושה את זה נכון. אז זה ההיבט החיובי של הטבע. אנחנו עושים טונות של שיקום, הרבה אגרו-אקולוגיה, אבל לא הכל הולך להיות בשביל למקסם את קיבוע הפחמן. אני חושב שזו נקודה ממש טובה שלפעמים אנשים מפספסים. אנחנו יכולים להיות עטופים מדי ברעיונות: אקלים, פחמן, קיבוע... אבל אז אנחנו קצת מתגעגעים לקטע הטבע. הנדיבים שלנו ב-Duke Farms אמרו בעצם שיש להשתמש בנכס הזה לטובת חיות הבר והחקלאות. אז, אנחנו לוקחים את מה שדוריס דיוק אמרה ומנסים לפרש אותו בהקשר של ימינו. וכאן נחתנו: להיות טבע חיובי ושלילי פחמן.

תגובות אחרונות